|

|  | Chronic Back & Leg Pain

Definition

Failed Back Syndrome (FBS) is clinically defined as persistent or recurrent

pain, mainly in the region of the lower back and legs, after lumbosacral

spine surgeries that are technically and anatomically successful. |

Epidemiology

Approximately 5% of people experience a new episode of low back pain each

year, and over a lifetime, 60%-85% of people will experience an episode

of low back pain (Svensson 1989; Frymoyer 1991; Papageorgiou 1995; Cassidy

1998). One-third of those patients experiencing

low back pain go on to develop chronic or recurrent low back pain (Hakelius

1970; Weber 1983).

Half of all spinal surgeries performed are lumbosacral (Segal 1998). Failed

back surgery occurs

in approximately 30% of these patients, in which "failure" is

defined by persistent or recurrent pain, with and without low back pain,

after anatomically successful surgery (Segal 1998; North 1994; North 1991a). |

Economic concerns

FBS sufferers represent a huge economic concern. Of more than 300,000 lumbosacral

surgeries performed annually in the U.S. (Segal 1998), approximately 100,000

new cases of FBSS are expected each year (Segal 1998; North 1991). FBS also

has a high prevalence in Europe.

In Belgium, for example, approximately 2,400 new patients present with FBS

each year

(population 10 million). With a typical FBSS patient having undergone at

least one previous lumbosacral operation, repeated lumbosacral operations

are successful in only 20%-30%

of patients, suggesting a worsening of their condition, in spite of, or

because of, surgery

(North 1991a; Fritsch 1996). Accordingly, FBS poses a huge therapeutic challenge. |

Symptoms

Patients with FBS may suffer from recurrent disc herniation, lumbosacral

postoperative fibrosis and/or arachnoiditis, epidural scarring, an injured

nerve root, dorsal compartment syndrome and/or lateral spinal stenosis.

Pain may arise from viscera, blood vessels, nerves, bones of the spine and

pelvis, muscles and/or joints. In most cases, a specific cause of the pain

associated with FBS cannot be identified. Physicians have even reported

cases in which patients who were admitted for surgical treatment of FBS

have subsequently been defined as having pain of a different origin. |

Causes

Several factors may contribute to this syndrome, including selection of

inappropriate patients for surgery (Spengler 1980; Zucherman 1986; Fager

1980; Long 1988), surgical complications, irreversible nerve injury and

psychosocial problems. |

Pain

Pain associated with FBS is thought to encompass a mixture of neuropathic

and nociceptive elements. The condition always involves the dorsal horn,

consisting of central sensitisation and mainly sympathetic involvement.

Pain that is primarily in the leg is thought to involve nociceptive pain

or neuropathic pain, or in some cases, a mixture of both types of pain.

In contrast, back pain

is thought to be the result of degeneration of intervertebral joints or

pseudoarthrosis, or an infection or degenerative change at other vertebrae.

For FBS sufferers, the pain associated with their condition remains typically

refractory, difficult to control and unlikely to respond to further reconstructive

surgery, suggesting that other treatments, such as neurostimulation, should

be considered. |

Current treatments

Recent clinical studies have focused on refining existing therapies for

FBS and identifying factors that could influence outcome and improve patient

selection criteria. |

Conservative

Conservative treatment is standard for most patients with chronic low back

pain. Treatment consists of a combination of physiotherapy (rehabilitation

and symptomatic treatment), oral medication, analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs and corticosteroids. Treatment

for obesity or depression might also be necessary. Patients are encouraged

to engage in normal physical activity as much as possible to prevent debilitation

due to prolonged rest. |

Orthopaedic surgery

Orthopaedic surgery normally involves interbody fusion (intervertebral implant);

surgical resection of disc herniation; discectomy, with or without interbody

fusion; and removal of a stenosis by decompressive surgery, with or without

interbody fusion. In patients with FBS, surgery is not usually suitable.

The success rate of repeated lumbosacral operations is only 20%-30% (North

1991a; Fritsch 1996). Many patients with FBS require multiple lumbar surgeries

before reporting clinical success and relief from pain, although some patients

never achieve pain relief. Thus, re-operation should be considered only

for those patients with FBS in whom pain can be attributed to a surgically

remediable lesion. In other patients with FBS who have had anatomically

successful surgery but still experience pain, the use of neurostimulation

has proved a more effective treatment option (North 1991a, 1991b). |

Neurostimulation and

intrathecal drug delivery

Neurostimulation and intrathecal drug delivery are minimally invasive, reversible

treatments for pain associated with FBS, compared with the sometimes destructive

and costly procedures of spinal surgeries. Recent technological advances

in neurostimulation and intrathecal drug delivery show that these treatments

are highly effective, suggesting that they should be used earlier. Patients

with low back pain usually respond well to neurostimulation, and this is

often explored before intrathecal drug delivery. The best indication for

neurostimulation is neuropathic pain of peripheral or nerve root origin.

Failure of a neurostimulation trial could indicate predominantly nociceptive

pain and should prompt an intrathecal drug delivery trial. |

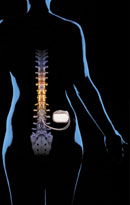

Neurostimulation

System |

Neurostimulation:

Neurostimulation is the treatment of choice for patients with FBS who suffer

from chronic neuropathic pain of a non-structural nature that is refractory

to conservative treatments. This therapy can be administered as either spinal

cord stimulation (SCS) or peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS). Of the two

techniques, SCS is much more widely used, with more substantial supporting

clinical data. SCS has been used as a method for relief of chronic pain

for more than 30 years, and involves electrical stimulation of the spinal

cord via implanted electrodes to produce paresthesia corresponding to the

areas of pain. The mechanism of action is still being elucidated. The most

commonly accepted theory is the gate-control theory of pain (Melzack and

Wall 1965). Other theories include inhibition of pain at the supraspinal

level and activation of central inhibitory mechanisms that influence sympathetic

efferent neurons. Conventional SCS techniques involve the implantation of

a single lead. One of the most challenging aspects of SCS has been the placement

of the electrode in a position that provides parasthesia to the painful

area without stimulation of the dorsal roots. |

| However,

technological advances using two leads have resulted in the potential to

steer the paresthesia and correct its coverage after implantation; for example,

by activating additional cathodes on the side with the weakest stimulation.

Other advances in the percutaneous placement of multiple electrode leads

have also yielded improved results. The development of neurostimulation

systems with more lead options and electrode spacing diversity has resulted

in improved clinical results and the ability to treat a greater number and

variety of patients. Recent clinical studies have shown promising results

for long-term pain relief with |

SCS

(Ohnmeiss and Rashbaum 2001; Kumar 1998; Kupers 1994; Burchiel 1996 and

Burchiel 1995 ). A prospective trial showed that SCS is superior to re-operation

as a treatment for FBSS (North 1994). Furthermore, at a recent advanced

workshop organized by the ECMT, Drs. Alo and Van Buyten agreed that the

availability of dual leads would reduce patient drop-out rates in those

patients with hard-to-treat pain conditions. SCS has also been shown to

improve performance

of activities of daily living (North 1993; De La Porte 1993). Importantly,

this treatment regimen is also cost-effective compared with re-operation

or long-term oral medication (Kumar 2002a; DeLissovoy 1997; Bell 1997; Kidd

1996). The most common issue arising from SCS treatment

is lead migration. This is generally managed by correcting lead placement.

Alternatively, by using an Octad lead, with 8 electrodes,lead migration

can be managed by reprogramming stimulation patterns to alternative electrodes

on the lead. |

Intrathecal Drug

Intrathecal Drug

Delivery System

|

Intrathecal drug delivery:

Long-term opioid therapy is a viable option for FBS patients with pain

of a predominantly nociceptive nature,or

for those patients who have failed a neurostimulation trial. For patients

with predominantly nociceptive pain, SCS is less likely to relieve pain

than in those patients whose pain is neuropathic. Intrathecal drug delivery

involves the spinal administration of opioids via an implantable, programmable

drug delivery system. Site-specific delivery reduces

the opioid dose that must be administered, compared with systemic methods,

with the consequence that there are fewer side effects. A number of studies

have shown positive outcomes following treatment with intrathecal drug

delivery in patients with FBS (Anderson and Burchiel 1999; Paice 1996;

Winkelmuller 1996; Tuktak 1996).

In addition, programmable pumps allow for easy post-do titrationse. Utilising

patient controlled analgesia (PCA) permits the titration of the analgesic

dose to the analgesic requirements within physician-set limits and allows

for the management of breakthrough pain.Additionally, intrathecal drug

delivery has been demonstrated to be cost-effective for the treatment

of FBS (Kumar

2002b) in patients who fail a neurostimulation trial

|

Treatment pathway for FBS

Neuromodulation is the treatment of choice for patients

with FBS who suffer from chronic pain of

a non-structural nature that is refractory to conventional treatment. |

Further reading

References:

|

- Anderson V,

Burchiel K. A prospective study of long-term intrathecal morphine in the

management of chronic

non-malignant pain.Neurosurgery 1999;44(2):289-300.

- Bell GK, et al. Cost effectiveness

analysis of spinal cord stimulation in treatment of failed back surgery

syndrome.J Pain Symptom Manag 1997;13:286-295.

- Burchiel K, et al. Prognostic

factors of spinal cord stimulation for chronic back and leg pain. Neurosurgery

1995;36:1101-11.

-

Burchiel K ,et al. Prospective, multicenter study of spinal cord stimulation

for relief of chronic back and

extremity pain. Spine 1996;21:2786-94.

- Cassidy DJ. The Saskatchewan Health and Back Pain Survey: the prevalence

of low back pain and related

disability in Saskatchewan. Spine;1998;23:1860-7.

-

De La Porte C, et al. Spinal cord stimulation in failed back surgery syndrome.

Pain 1993;52:55-61.

- DeLissovoy G, et al. Cost-effectiveness of long-term intrathecal morphine

therapy for pain associated with

failed back surgery syndrome. Clin Ther 1997;19:96-112.

- Fager CA, Freidberg SR. Analysis of failures and poor results of lumbar

spine surgery. Spine 1980;5:87-94.

- Fritsch EW, et al. The failed back surgery syndrome: reasons, intraoperative

findings, and long-term results:

a report of 182 operative treatments. Spine 1996;21:626-33.

- Frymoyer JW and Cats-Baril WL. An overview of the incidence and costs

of low back pain.

Orthop Clin North Am 1991;22:263-71.

- Kidd D, et al. Spinal cord stimulation: an effective and cost-saving

treatment in the management of chronic pain.

In: Pain Treatment Centers at a Crossroads: A Practical

and Conceptual Reappraisal.

- Cohen M and Campbell J, eds. IASP Press: Seattle, 1996, p.176.

- Kumar K, et al. Epidural spinal cord stimulation for treatment of chronic

pain - some predictors of success.

A 15-year experience. Surg - Neurol 1998;50:110-21.

- Kumar K, et al. Treatment of chronic pain with spinal cord stimulation

versus alternative therapies:

cost-effectiveness analysis. Neurosurgery 2002;51:106-116.

- Kumar K, et al. Treatment of chronic pain by using intrathecal drug

therapy compared with conventional pain

therapies: a cost effectiveness analysis. J Neurosurg

2002;97(4):803-810.

- Long DM, et al. Clinical features of the failed-back syndrome. J Neurosurg

1988;69:61-71.

- Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain Mechanisms: a new theory. Science. 1965;150:971-9.

- North RB, et al. Failed back surgery syndrome: 5-year follow-up after

spinal cord stimulator implantation.

Neurosurgery 1991a; 28:692-9.

- North RB, et al. Failed back surgery syndrome: five-year follow up in

102 patients undergoing reoperation.

Neurosurgery 1991;28:685-91.

- North R, et al. Spinal cord stimulation for chronic, intractable pain:

experiences over two decades.

Neurosurgery 1993;32:384-95.

- North RB, Kidd DH. A prospective randomised study of spinal cord stimulation

versus re-operation for failed

back surgery syndrome: initial results. Stereotact

Funct Neurosurg 1994; 62:267-72.

- Ohnmeiss DD, Rashbaum RF. Patient satisfaction with spinal cord stimulation

for predominant complaints of

chronic, intractable low back pain.Spine J 2001;1:358-63.

- Paice J, et al. Intraspinal morphine for chronic pain: retrospective,

multicenter study.

J Pain Symptom Manag 1996;11:71-80.

- Papageorgiou AC, et al. Estimating the prevalence of low back pain in

the general population:

evidence from the South Manchester back pain survey.

Spine 1995;20:1889-94.

- Segal R, et al. Spinal cord stimulation revisited. Neurol Res 1998;

20:391-6.

- Spengler DM, et al. Low-back pain following multiple lumbar spine procedures:

failure of initial selection?

Spine 1980;5:356-60.

- Svensson HO, Andersson GBJ. The relationship of low-back pain, work

history, work environment, and stress:

a retrospective crosssectional study of 38

to 64 year old women. Spine 1989;14:517-22.

- Tutak U, et al. Intrathecal infusion systems of chronic low back and

leg pain of noncancer origin.

South Med J 1996;89:295-300.

- Winkelmuller M, et al. Long term effects of continuous intrathecal opioid

treatment in chronic pain of

nonmalignant etiology. J Neurosurg 1996;85:458- 467.

- Zucherman J, Schofferman J. Pathology of failed back surgery syndrome.

In: White AH, ed. Failed back surgery syndrome.Philadelphia:Hanley

& Belfus, 1986: 1-12.

|

|

|

|